The need for complementary actions to support positive sexual health outcomes for young people are well-documented, and should take place across a number of key domains. The five domains are:

- laws, policies and human rights

- education

- society and culture

- economics

- health systems

Laws, policies and human rights

Affirmative legal or policy interventions are critical for supporting existing sexual health interventions or for introducing new ones. Countries may use laws, policies and other regulatory mechanisms that are enshrined in international treaties to guarantee the promotion, protection and provision of sexual health information and services, and to uphold the human rights of every person within their borders.

Education

The correlation between education level and sexual health outcomes has been well documented. One of the most effective ways to improve sexual health in the long-term is a commitment to ensuring young people are sufficiently educated to make healthy decisions about their sexual lives. Accurate, evidence-based, appropriate sexual health information and counselling should be available to all young people, and should be free of discrimination, gender bias and stigma. This reality provides among the strongest rationales for integrating CSE in schools.

Society and culture

Social and cultural factors can be significant in determining access of people to sexual and reproductive health services and information. The influence of traditional values, beliefs and norms must not be underestimated. They affect the family, the community and society, and play an important part in shaping people’s sexual lives. While the sociocultural determinants of sexual health outcomes vary in time and place, it seems that the groups in society that have relatively little power have poorer sexual health, often because they have poor access to information and services or legal redress. Gender-influenced power relations, for example, have a significant effect on the sexual health of many women and girls. Link the CSE programme with community-based organisations or networks of people with diverse SOGIE or of PLHIV, etc. so that learners can get direct information from them and educators are not burdened with having to conduct conversations about 'difficult' issues all by themselves.

Economics

Poverty and economic inequality are intrinsically linked to poor sexual and reproductive health outcomes. These links are multi-directional, in as much as people living in poverty experience worse sexual and reproductive health than those in a better economic situation, and poor health leads to poverty. Financial necessity is often a driving force behind some forms of high-risk sexual behaviours. Health interventions can therefore only be effective if the relationships between a person’s economic needs, vulnerability and health outcomes are fully understood and addressed, in both the short and the long term. Creating links with self-help groups or income-generating activities might enhance the effectiveness of the CSE programme when it is reaching young people who live in poverty.

Health systems

Accessible, acceptable, affordable and good-quality sexual health services are fundamental to achieving a sexually healthy society. Interventions to maintain and ensure sexual health have been shown to work best when they are offered to people of all ages, throughout their lifespan, regardless of their marital status. It is also important to make efforts to target young people in particular because of their social and biological vulnerability. Providers should be trained to screen and detect sexual health problems and provide appropriate educational information about prevention, counselling, treatment, care and referral.

(Excerpted and adapted from: World Health Organization, 2010 – “Developing Sexual Health Programmes: A Framework For Action”)

CSE that includes community-based components – including involving young people, parents and teachers in the design of interventions – results in the most significant change. Research has made apparent the need to link the provision of CSE and other complementary interventions to SRH services. This includes the need to:

-

build awareness, acceptance, and support for youth-friendly CSE and SRH services among clients and their gatekeepers;

-

address gender inequality in terms of beliefs, attitudes, and norms;

-

target younger learners, in particular, those in the early adolescent period (10-14 years);

-

ensure health care providers are trained and supported in youth-friendly delivery of services, including being non-judgmental and friendly; and

-

ensure that health facilities are welcoming and appealing to young people.

(Source: UNESCO, 2017 – “CSE Scale-Up In Practice”)

Partnerships

At the local level, coordinating CSE with complementary programmes can involve two main efforts: The first is to do a scan of a community or area to determine what is currently being offered to avoid duplicating efforts. The second is to determine whether and how partnerships may be available in order to maximize the impact of CSE, whether as a stand-alone or a programme integrated into other programmes and services.

Three types of partnerships include:

-

Leverage/Exchange partnerships are those in which each partner brings discrete skill sets or resources to complement the other. For example, a community may be prepared to provide in-person teacher training on CSE, but is not up-to-date on trauma-informed approaches. It would help to partner with a local organisation with expertise in that area to provide a co-facilitator or guest speaker to participate in the training.

-

Combine/Integrate partnerships are partnerships in which the entities are engaged from and invested in the programme from the beginning. These partnerships require much more planning up front, as they also involve discussing and sharing resources. For this reason, these partnerships are most effective when a sufficient amount of time is built into the process to build trust and collaboration, or when the partner is a known entity with which a school/community organisation may have had previous experience.

-

Transform partnerships are those involving numerous partners and an approach that is not necessarily set and agreed upon in advance. The direction may emerge, change or evolve as the process moves forward. As such, partners need to check in and negotiate parameters of the partnership and initiative goals on a regular basis.

(Source: The Partnering Initiative and UN DESA, 2019 – “Maximising the Impact of Partnerships for the SDGs: A Practical Guide to Partnership Value Creation”)

Tips for Establishing Community Partnerships

The UNICEF Strategic Framework for Partnerships and Collaborative Relationships

points to five criteria that underlie successful work with partners:

-

Equality

-

Transparency

-

Results-oriented

-

Responsibility

-

Complementary

The Strategic Framework further highlights the need for explicit agreements, regular review,

monitoring and evaluation, conformity to existing rules and procedures that reinforce

equality and transparency, and an exit process that can lead to discontinuation of a

partnership if necessary.

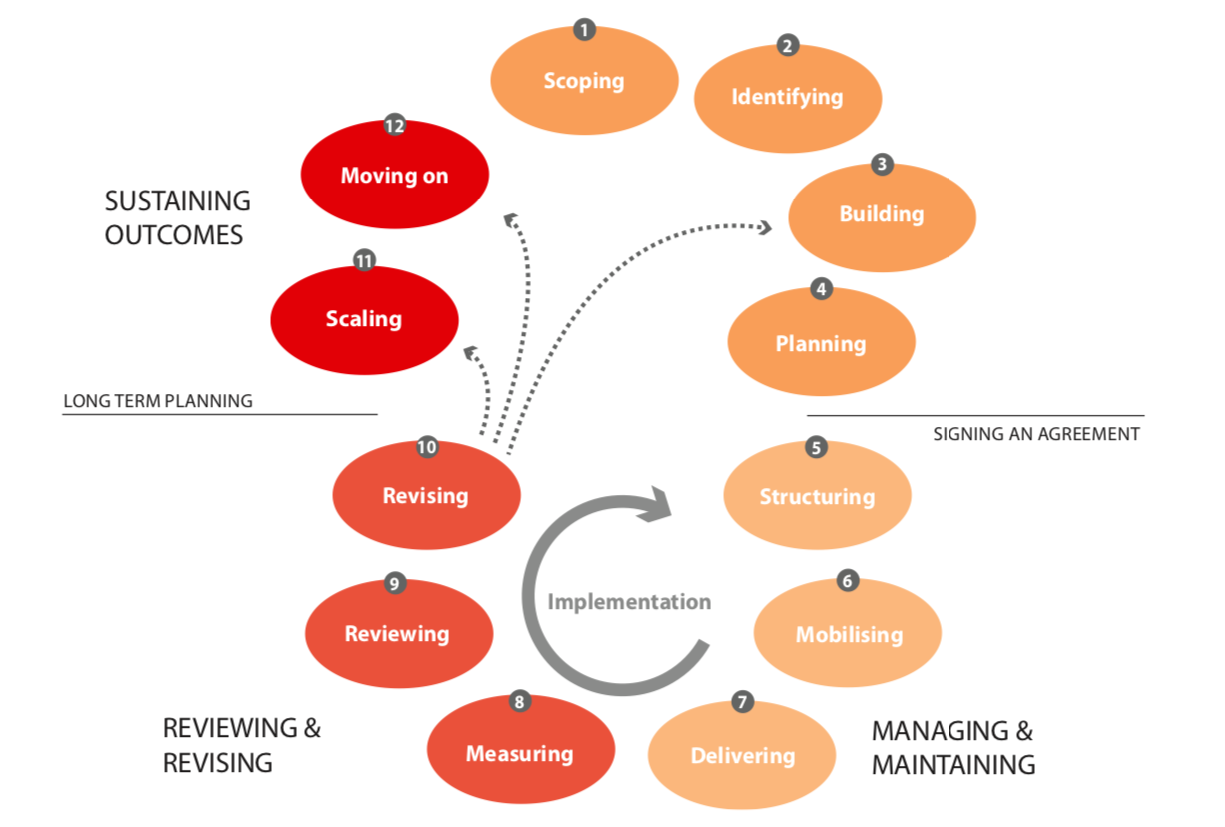

The figure below is a model of the main stages that a typical cross-sector collaboration will move through: